In March

2011, Sunni Arab Gulf states, led by Saudi Arabia, swept over the bridge into

Bahrain to help crush the predominantly Shiite but democratic and

reform-oriented protest movement. The wide-ranging campaign of sectarian

repression that followed destroyed a U.S.-facilitated reconciliation mission

between the Bahraini crown prince and the leading opposition parties.

Washington

then watched as the inevitable unfolded in a key Gulf ally — repression with

impunity, persistent instability, rampant sectarianism, the likely permanent delegitimization

of the regime, and a denunciation of the U.S. role by both sides. Its failure

to respond defined American hypocrisy about the Arab uprisings in the eyes of

many across the region, and helped give a green light to autocrats to crack

down on their challengers. More than two years later, Bahrain’s continued street

protests and growing radicalism suggests how little the crackdown served the

cause of stability.

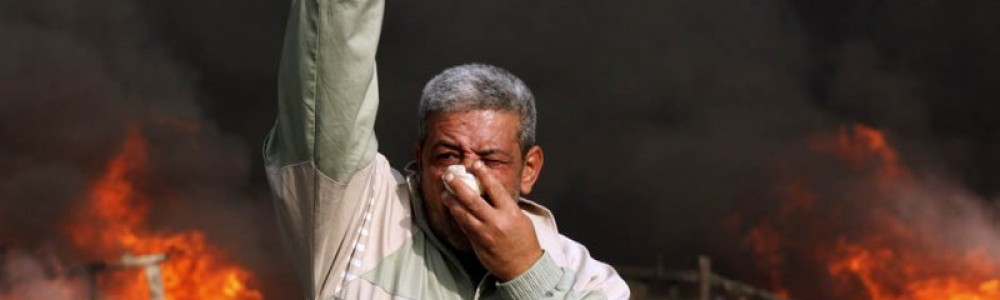

While

events in Cairo are of course very different, the risks for Washington are similar.

Once again, the United States seems helpless as a crucial ally — in this case

the Egyptian military — recklessly flaunts democratic norms. The persistent

instability and disillusionment with the democratic process likely to follow the

coup was obvious even before this week’s violent clashes and Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s

alarming

call for mass protests in support of a new “war on terror” against the

Muslim Brotherhood. Once again, Washington seems torn between its hope for

democratization on the one hand, and its distaste for the aggrieved parties (Muslim

Brothers in Cairo, possibly Iran-backed Shiites in Bahrain) and strategic ties

to the ascendant authoritarians on the other.

Faced

with this dilemma, Washington has tried to hide. President Barack Obama’s

administration will reportedly

tell lawmakers that it does not consider an obvious coup in Cairo to be a

coup, and that its annual aid to Egypt will keep flowing. Secretary of State John

Kerry bafflingly mused that the military might have prevented a civil war,

which is a defensible

analytical position but not the sort of thing that a senior U.S. official

should be saying aloud. Finally, the White House belatedly announced it was suspending

the delivery of four F-16s

to the Egyptian military — but declined to suspend a major joint military

exercise or its $1.3 billion in annual aid.

It’s

easy to understand why the United States hedged its bets. The mass protests on

June 30, the July 3 coup, the escalating Muslim Brotherhood protests, the

dissolution of virtually all political institutions, and this week’s seemingly

unstoppable charge toward full-scale repression have seemingly shattered America’s

roadmap for the country’s transition to democracy. With the military in charge and

politics driven by competing street protests, there are no longer any

established rules to the political game. And things weren’t going well even

before the coup: Egypt’s economy was in free-fall, street clashes were

increasingly violent, and many Egyptians were deeply alarmed by the unilateral

and majoritarian behavior of Mohamed Morsy’s government.

It’s not

like Egyptians particularly want Washington to do anything, either. Its

politicians and public figures instead unanimously tell the United States to

buzz off and mind its own business. The wave

of anti-Americanism that swept Cairo’s streets in the wake of the military

takeover, no matter how politically motivated, has to be disturbing for a White

House that prided itself on reaching out to newly empowered Arab publics. But quite

frankly, a lot of people in Washington seem downright relieved to be rid of the

troublesome Muslim Brotherhood and the endless crises of attempted

democratization, and happy to just get

back to working with a friendly military regime. A new Mubarakism may not be

pretty, but it doesn’t look so bad to a lot of Americans exhausted by the

region’s chaos.

At this

point, the number of people who really believe the United States supports

Egyptian democracy would probably fit around a Washington think-tank conference

room table. But I would be one of those around that table — U.S. policy toward

Egypt isn’t quite the disaster it appears. America’s goal of helping to create an

institutionalized Egyptian democracy was the right one, and its low-key approach

accurately reflected its limited ability to shape events. U.S. officials

understood that Egypt’s future would be shaped by Egyptians, and that not many

Egyptians anxiously awaited a White House statement to decide what to think

about their political crisis.

Open all references in tabs: [1 – 7]