In Bahrain we hardly hear the moderates speaking out. The loudest voices in our society are different brands of religious hardliners, who in reality only represent a small fraction of our diverse and tolerant society.

The problem isn’t that most Bahrainis are sympathetic to extremist ideas – they aren’t. Rather, the problem is that it is the extremists who are most assertive in promoting their agenda and pressuring others to follow them.

For example, when an Islamist MP stands up in parliament and argues that non-Muslim products like pork and alcohol should be banned, most of us wouldn’t dare contradict him because we are Muslims and they justify their arguments on religious grounds. Nobody wants to be accused of being a bad Muslim.

Yet, over half of those living in Bahrain are non-Muslims and most of us instinctively feel that their beliefs and practices should be respected – but we don’t speak out in defence of our non-Muslim brothers and sisters.

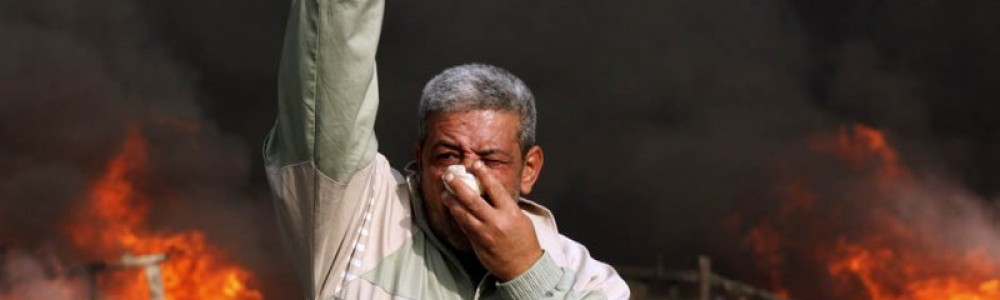

During the 2011 unrest, when many of us spoke out in public or in the social media – calling for restraint or condemning sectarian insults – we were attacked by figures on both sides.

The result was that most liberals and moderates – the middle ground of Bahrain society – simply stopped talking. We detested the sectarianism, the violence, the extremism and the intolerance; but we only expressed our views in the privacy of our homes. The result was that we surrendered the public domain to extremists and intolerant voices, on both sides of the opposition and loyalists.

Many moderates initially came out in support of the 2011 protests calling for reform, social justice and condemning corruption. But those liberals, intellectuals, middle classes and progressives were quickly alienated by the sectarian and theocratic leaders of the opposition movement who wanted to topple the monarchy and establish a republic on sectarian Islamic principles.

So moderates on both the loyalist and opposition sides, as well as those who sympathise with neither movement, found themselves without a voice.

This is not a normal situation for Bahrain.

The benefits of Bahrain’s relatively new Constitution – His Majesty King Hamad’s 2001 National Action Charter – included its aspiration to consolidate a nation for all its citizens, whatever their faith or background. All should enjoy equal rights and opportunities.

The benefits of Bahrain’s Constitutional Monarchy include its ability to counterbalance sectarian tendencies – so that even if Islamist political societies like Shia Al Wefaq or Salafist Al Asala gain numerous parliamentary seats, they cannot Islamise society overnight or extinguish the rights of other sects and religions.

The Shura Council, made up of royal appointees, contains a diverse mix of sects, religions and tendencies and acts as a counter-balance to the directly elected half of the parliament. Therefore, between the two houses of parliament, judiciary and the government, Bahrain enjoys a division and a balance of power, which prevents any particular sect or tendency from forcing its vision on everybody else.

The opposition led by Al Wefaq National Islamic Society wants a single house of parliament and a directly elected government, and many of its supporters are agitating for complete abolition of the monarchy.

They argue that this would make Bahrain fully democratic.

But the obvious result of these measures is that whichever sect best succeeds in mobilising its supporters would come to dominate the presidency, the government and the parliament.

This is effectively what happened when the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt defeated all other parties in the last elections and came to dominate all political institutions, except the army.

It is also what happened in post-2003 Iraq where Shia political groupings progressively marginalised and alienated Sunnis, fundamentally undermining and delegitimising the democratic process.

A sectarian-based power-sharing system in Lebanon effectively ensures that groups like Hizbollah are entrenched in positions of power and many of the most influential positions are held by civil war-era warlords or their offspring. Such systems make it virtually impossible for liberals and religious minorities to be heard and for their rights to be secured.

If moderates are empowered, they generally act to secure the rights of all components of society. When extremists are empowered, they always act to marginalise and disempower all other sections of society.

A fundamental paradox of democracy is that the democratic system can be exploited by anti-democratic groups who can use it to attain power and then destroy these democratic institutions.

In the Arab world, Islamist groups with poor democratic credentials have always tended to perform well in elections. When they failed, they have often resorted to terrorist tactics to attain power.

The failure of democratic experiments in Egypt, Iraq and elsewhere lead to the inevitable conclusion that in our complex and diverse societies a more robust political system is required which enshrines the rights of all citizens and guards against the sweeping to power of popularist but intolerant and socially regressive groups.

While Egyptians take to the streets over support for an Islamist or secular vision for their nation, the economy continues to suffer; poverty and unemployment grow; and ordinary citizens suffer.

We need to develop systems of governance where the views of all citizens are represented and all are given a voice, but where nobody – including the political leadership – is allowed to trample on the rights of others.

In Egypt, Iraq and Syria, it is doubtful whether such a model can easily be achieved. In Bahrain, if all sides genuinely come together for a process of National Dialogue, such a vision is not beyond our reach.

However, this means curtailing the ambitions of both radical Sunnis and Shia, who reject the rights of other citizens and fail to respect alternative views.

In order for such a vision to be realised, Bahrain’s moderates must stand up.

Only by preserving the constitutionally-enshrined balance of power and by ensuring a strong moderate voice can all components of Bahraini society enjoy their political, social and religious rights.

Citizens for Bahrain